No-Scalpel Vasectomy

and Open-Ended

Table of Contents

The Terminology

No-Scalpel Vasectomy

The Tubes

Upper End & Lower End

Each of the two tubes is divided, leaving two ends.

The upper end is the end nearest the groin, referred to as the abdominal end. The lower end is the end nearest the testicle, referred to as the testicular end.

The Fascia

Fascial Interposition

Open-Ended Vasectomy

Animation Video

What is No-Scalpel Vasectomy?

Getting to the Vas Deferens

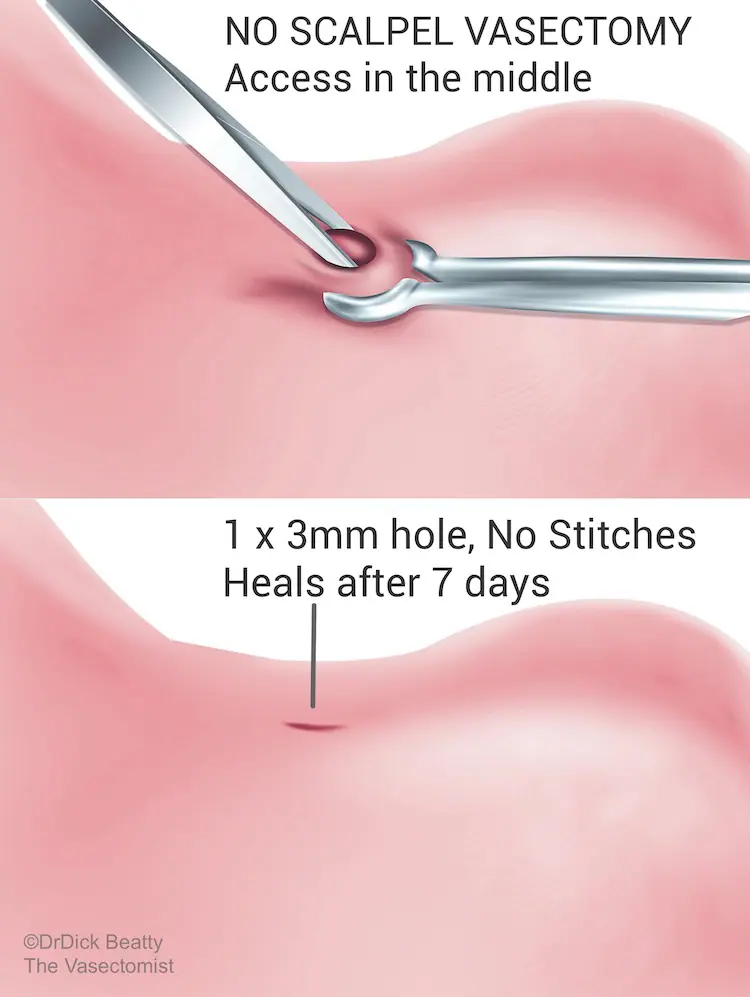

No-scalpel vasectomy (NSV) is the best method to gain access to The Vas Deferens. An important yet often overlooked fact is that NSV describes how to get to the tubes—no more and no less.

A 3 mm hole is made in the upper-middle part of the scrotum, and then a loop of the vas deferens is brought up and out through the skin. NSV is ‘minimally invasive’ but not keyhole surgery; surgery is performed outside of the body.

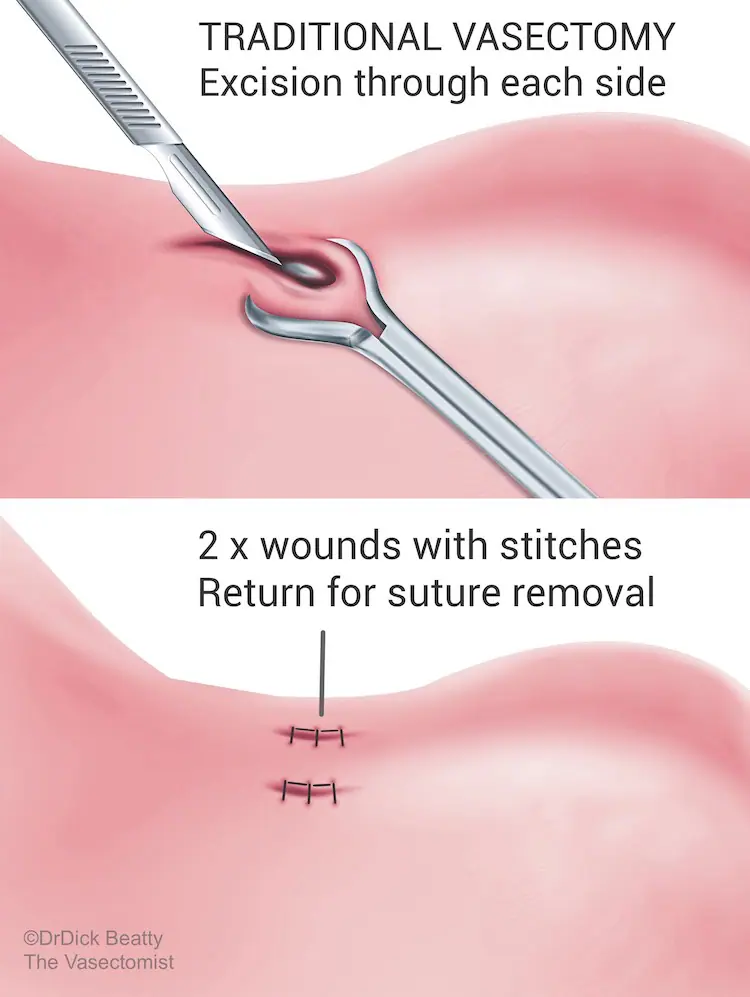

NSV leaves a small 2-3mm hole at the front of the scrotum. No stitches are required, so you don’t have to return for stitch removal. Minimal tissue trauma means you can return to work and physical activities sooner. In comparison, traditional vasectomy requires incisions and stitches on both sides of the sac.

The guidelines

No-scalpel vasectomy is recommended above traditional vasectomy in the leading American Urological Association Vasectomy Guideline, which states explicitly in its amended 2015 guideline that ‘Minimally Invasive Vasectomy should be used for Vas Isolation.’

The UK Vasectomy guideline (FSRH 2014) states that ‘a minimally invasive approach should be used to expose and isolate the Vas Deferens during vasectomy as this approach results in fewer early complications in comparison to other methods.’

The European Association of Urology Guidelines on Vasectomy guideline (2012) adds to the consensus: ‘The no-scalpel vasectomy technique of isolation of the vas deferens is associated with fewer early complications.’

How are the tubes blocked?

With the tubes now accessed using the No-scalpel method, let’s look at how to block them.

Snipping the tubes

Vasectomy is widely known as ‘The Snip’ – suggesting that the tubes simply be cut. Sounds simple, right? We know that cutting and removing the vas results in a failure rate of just under 10%. You can imagine that cutting the tube without doing anything else will not be a happy ending.

The tubes are cut, but they are also blocked. Let’s introduce the vasectomy buzzword that separates one vasectomy method from another: Occlusion.

What really separates types of vasectomy is the method of occlusion

Blocking the Vas Deferens

Different methods of occlusion are:

- Electrocautery to the internal lining of the tube (the lumen) – with a machine that looks a bit like a laser.

- Thermal cautery to the lumen (cautery using heat) – typically with a simple battery-operated pen device.

- Fascial interposition (capping the end of the tube with its outside lining called fascia).

- A combination of cautery and fascial interposition.

Time to introduce open-ended and closed Vasectomy.

Closed versus open-ended

After cutting the tube, you will have two ends. Should you block the upper end, the lower end, or both? This is where things get a little convoluted (incidentally, a bit like the lower end of the tubes – which is why the incision is in the upper part of the scrotum).

Let’s look at two scenarios: blocking the lower end versus blocking the upper end.

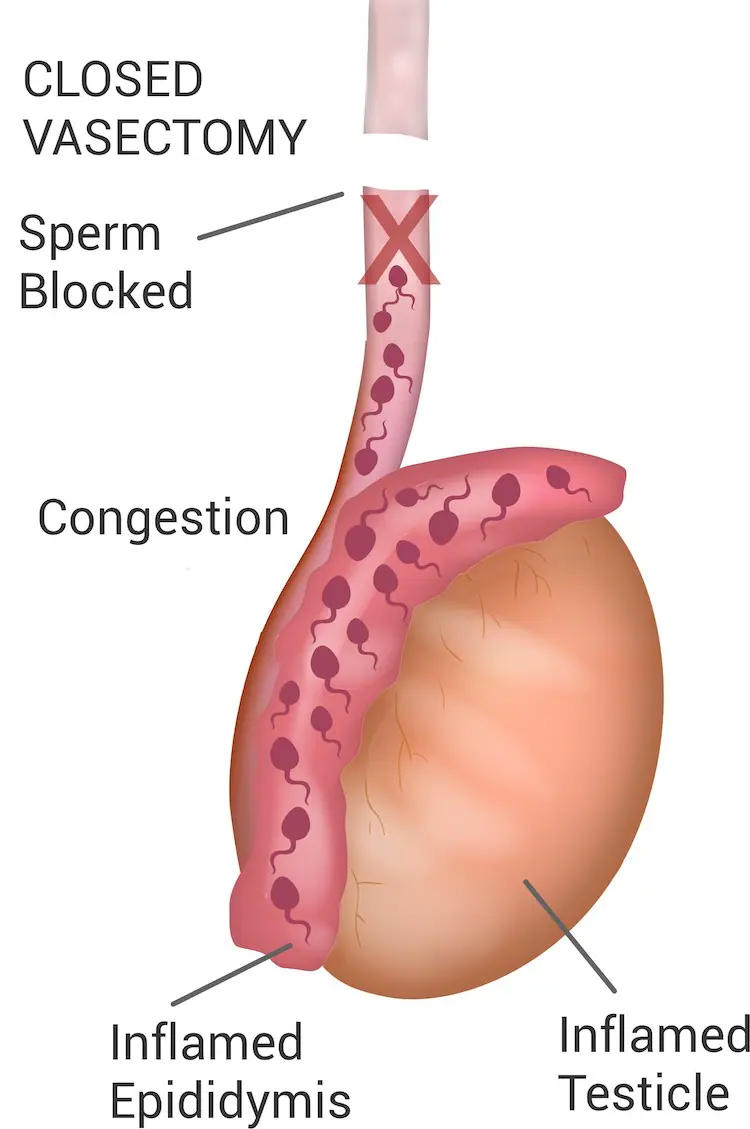

Closed Vasectomy

A closed vasectomy involves cauterizing the lower end of the vas deferens, which prevents sperm from being transported from the testicles. This blockage can lead to discomfort commonly referred to as ‘blue balls’ due to back pressure.

Note that you can’t just cauterize one end and leave the other open, or the tubes have a 10% risk of growing back. Closed Vasectomy, therefore, requires both the upper and the lower end to be occluded – typically with electrocautery.

Open-ended Vasectomy

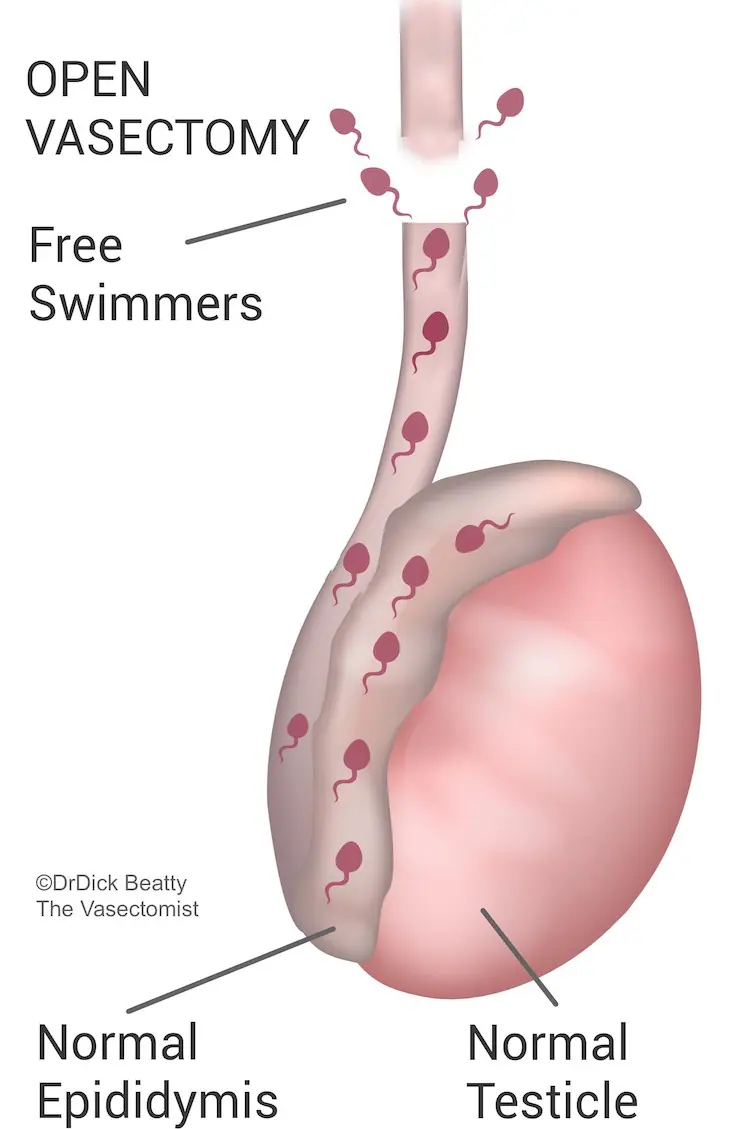

The open-ended method blocks only the upper end, leaving the lower end open. In theory, sperm can swim upstream from the testicle through the open end, reducing congestion.

As mentioned, cauterizing only one end (in this case, the upper end) while leaving the other intact is a recipe for failure. However, cauterising the lower end would not be open-ended. What else can you do to the upper end to ensure the vasectomy works? The answer is what makes open-ended vasectomy possible: Facial Interposition.

For two reasons, leading Vasectomists regard Facial Interposition (FI) as the gold-standard vasectomy occlusion method. Firstly, FI allows for an open-ended vasectomy, and secondly, the failure rate is very low.

Post-procedure pain

You might imagine that sperm swims out of the lower tube after an Open-Ended Vasectomy. However, an experiment in rats demonstrated that the open tube does close within a few weeks. However, closure would undoubtedly be slower than the abrupt closure following a closed vasectomy.

Research comparing open-ended to closed vasectomy suggests that the open-ended method does indeed result in less post-vasectomy discomfort. However, research is not 100% conclusive, which explains why vasectomy guidelines do not (yet) categorically state that open-ended is better than closed vasectomy.

Success rate

Furthermore, Open-Ended Vasectomy (AKA Fascial Interposition) improves the success rate of vasectomy while cautery to both the upper and lower ends is more likely to fail – particularly if the use of cautery is minimised. Aggressive cautery is more difficult to reverse and takes longer to heal than Open-Ended Vasectomy.

Closed Vasectomy fails almost 1% of the time, according to a UK audit of mostly closed vasectomies.

Vasectomists who have performed both open-ended and closed vasectomies will usually continue with the open-ended method. Failure rates of less than 1 in 500 are achievable – under the <1% quoted in some guidelines.

Open-ended vasectomy is considered to be the gold standard method of occluding the vas deferens.

Fascial Interposition

Open-vasectomy is made possible by Facial Interposition (FI), a technique that separates the upper from the lower end.

The Method

Fascia is a strong, thin, separate structure that encases and sticks to the outside of the Vas – a bit like the ‘skin’ of a sausage.

A loop of Vas, held by forceps, is brought out through the small skin incision, explaining a slight ‘lifting’ or ‘pressure’ sensation. Approximately 2-4cm of fascia is pulled and/or dissected away from each side of the forceps. The objective is to obtain a clean loop of Vas without any fascia stuck to it.

The Vas is now cut above the forceps still holding up the lower end. As a result, the upper end drops back down towards its fascial layer. The fascia is gently pulled over the upper end and held in place with a titanium clip or absorbable suture—like tying the end of a thin sausage (the tube is 3-5mm in diameter).

As a result, the upper end is covered with its fascia, while the lower end has been stripped of its fascia. In other words, the fascia ‘interposes’ the upper and lower ends; hence, ‘fascial interposition.’

Fascial Interposition is a more effective method of occlusion than cautery. Cautery of the upper end is often combined as insurance against occlusion failure. However, FI is very effective on its own, and cautery is probably not required.

Performing FI takes more time and is technically more difficult than cautery. Bleeding may occur from the deferential artery that lies within the fascia.

The saying ‘A stitch in time saves nine’ has a certain ring to it when you think of fascial interposition!